The question raised was whether the actual malice doctrine should be expanded even to non-public officials, but whose influence and notoriety would equal that of public officials.

Thus in Curtis Publishing Co. versus Butts 388 U.S. 130 (1967), the Supreme Court tackled the issue as to whether the actual malice standard should be applied to public figures, a different class of plainitffs in defemation cases.

The Supreme Court ruled in the affirmative.

Below is a digest of the ruling in Curtis Publishing versus Butts.

Curtis Publishing Co. versus Butts

388 US 130 (1967).

Facts:

Two different cases with striking similarity in circumstance prompted the court to treat them in a single decision.

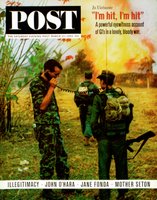

Two different cases with striking similarity in circumstance prompted the court to treat them in a single decision.The first case involved an article published in Curtis Publishing Company's Saturday Evening Post which accused James Wallace "Wally" Butts Jr., an athletic director of the University of Georgia, of “fixing” a football game between the University of Georgia football team and the that of the University of Alabama.

Butts here was employed by a private corporation and not by the State of Georgia. He had served as a football coach in the University and was well-known figure in the coaching ranks.

The defamatory article stated that Butts “rigged” a football match by revealing the game plan of the Georgia team.

The basis of the story was the testimony of a salesman who was

able to overhear the conversation of Butts and another person to whom Butts purportedly “spilled the beans.” To this Wally Butts sued Curtis Publishing and was awarded compensatory and punitive damages. The case reached all the way to the US Supreme Court.

able to overhear the conversation of Butts and another person to whom Butts purportedly “spilled the beans.” To this Wally Butts sued Curtis Publishing and was awarded compensatory and punitive damages. The case reached all the way to the US Supreme Court.The second case, Associated Press vs. Walker, 389 U.S. 28 (1967) arose out of news dispatch released by the petitioner Associated Press, about a rioting in the University of Mississippi.

The dispatch stated that respondent retired U.S. Army General Edwin A. Walker, who was present during the event, took command of the violent crowd and personally led a charge against authorities. Walker was reported to have encouraged the rioters to use violence.

The AP reported that Walker had “assumed command” of rioters at the University of Mississippi and “led a charge of students against federal marshals” when James H. Meredith was admitted to the university in September 1962. Walker alleged those statements to be false.

The AP reported that Walker had “assumed command” of rioters at the University of Mississippi and “led a charge of students against federal marshals” when James H. Meredith was admitted to the university in September 1962. Walker alleged those statements to be false.It was reported that "In the heat of the battle, an Associated Press reporter called the AP’s Atlanta bureau to report a famous man — retired U. S. Army General Edwin Walker — was giving technical advice on tear gas to the rebels. The general, he said, was leading and encouraging the charges at the Old Miss administration building. A bulletin was quickly teletyped. The story was published all over the world.

Walker was a private citizen at the time of the riot and publication. He had a career in the US Army before engaging in political activity. Walker was fairly deemed as a man of some political prominence.

Because of the news dispatch, Walker sued the Associated Press. Walker received a favorable verdict in a Texas state court, prompting the Associated Press to elevate the case all the way to the US Supreme Court.

In the High Court, Curtis and Butts and Associated Press in Walker raised constitutionals claims of the freedom of the press. Both argued that the actual malice doctrine in Sullivan should be extended to them.

Issue:

Whether or not the actual malice standard is to be applied even to public figures.

Held:

Yes. The Actual malice standard is applicable to public figures.

A greater majority of five justices were of the opinion that defamation cases involving public figures as plaintiffs must be measured against the actual malice standard laid down in New York Times v. Sullivan.

In his concurring opinion, Mr. Chief Justice Warren adhered to the standard in the Sullivan, which is actual malice, even to cases involving public figures.

He reasoned out that there is no basis of differentiating between “public figures” and “public officials.” As a matter of fact, he explained, both types of plaintiffs are intimately involved in the resolution of important public questions, or by reason of their fame, shape events in areas of concern to society.

“Public figures” like “public officials,” often play influential role in ordering society. “Public figures” too, like “public officials” have ready access to mass media in order to influence or counter criticism.

On the basis of the pronouncements of the members of the US Supreme Court, it reveals the interpretations of the New York Times v. Sullivan ruling on the First Amendment was meant to apply not only to “public officials,” but also to “public figures.”

Meaning of Public Figure

The United States Supreme Court described public figures thus: Public figures are characterized as those who command a substantial amount of independent public interest.

Both commanded sufficient public interest and had sufficient access to the means of counter-argument to be able to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies of the defamatory statements.

A public figure has been defined as a person who, by his accomplishments, fame, or mode of living, or by adopting a profession or calling which gives the public a legitimates interest in his doings, his affairs, and his character. He is in other words a celebrity. It covers everyone who has arrived

at a position where public attention is focused upon him as a person

No comments:

Post a Comment